MEDICINA PERSONALIZADA DE PRECISIÓN - VERSIÓN EN EPAÑOL

1 MEDICINA PERSONALIZADA

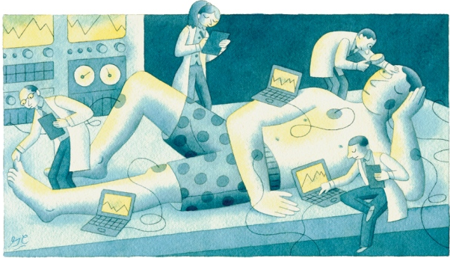

Más del seis por ciento de las admisiones de agudos al hospital son causadas por reacciones adversas serias debido al uso de fármacos. La mayoría de las medicinas comunes para un tratamiento no son efectivas en un largo número de pacientes. Las drogas utilizadas para tratamientos específicos no son efectivas para todos los pacientes o para cada grupo de pacientes como se esperaba (1-12). La medicina personalizada aborda este desafío, con una medicina de prevención “tailor-made” y tratamientos estratégicos para individuos o grupos de individuos. Como resultado, tenemos una situación donde todos ganan o “win-win situation” donde pacientes reciben terapias específicas que funcionan mejor para ellos y se gasta menos dinero en los ensayos clínicos y en los respectivos errores de tratamientos. El control del gasto de la salud pública es muy importante desde que los costos alrededor del mundo están incrementándose y la población envejeciendo. También, las enfermedades crónicas se han incrementado y otras enfermedades se trasmiten más rápidamente en la actualidad como consecuencia del aumento de la movilidad de la población mundial.

El concepto de “medicina personalizada” fue anticipado a fines del 1800s por el físico canadiense Sir William Osler quien notó “una gran variabilidad entre los individuos”; sin embargo, una definición más moderna involucra e incorpora el concepto de información genómica personal en las evaluaciones de los pacientes clínicos y su historia familiar para guiar la administración medica correspondiente (13-15). En la actualidad la investigación en el área incluye la identificación de las bases genómicas de las enfermedades comunes, el estudio de como los genes y el ambiente interactúan para ocasionar una enfermedad en particular y utiliza marcadores para facilitar aún más el uso efectivo de las terapias que involucran medicamentos (16).

Se acepta la definicion de Horizon 2020 Advisor Group que define la medicina Personalizada como “un modelo médico que utiliza la caracterización de los fenotipos individuales y genotipos (por ejemplo: los datos arrojados por el perfil molecular, las imágenes médicas y el estilo de vida) para “tailoring” la correcta estrategia de tratamiento terapéutico para la persona en el tiempo adecuado, y/o para determinar la predisposición a la enfermedad y/o el tiempo de entrega y determine la prevención adecuada “. Esta definición fue utilizada también por EU Health Ministers en sus conclusiones sobre medicina personalizada publicada en diciembre del 2015. Aunque algunas aproximaciones sobre medicina personalizada han sido incorporadas dentro de la práctica en Europa, aún están en un período temprano de implementación. Un cambio de paradigma significativo está tomando lugar en la investigación médica y el cuidado de la salud para que esta área innovadora sea explotada completamente.

2 MEDICINA DE PRESICIÓN

En la actualidad, el National Research Council (NRC) de Estado Unidos, considera medicina personalizada como un antiguo término y prefiere utilizar “medicina de precisión”. Para el NRC, la medicina de precisión es “una aproximación emergente para el tratamiento y prevención de las enfermedades que toman en consideración la variabilidad genética, el ambiente y el estilo de vida de cada persona”.

Existe una superposición entre las definiciones de medicina de precisión y la personalizada. Sin embargo, existe preocupación de que el término “personalizada” puede ser malinterpretada como tratamientos y prevenciones que están siendo desarrolladas únicamente para cada individuo. En la medicina de precisión, el foco es sobre identificar cuales aproximaciones pueden ser efectivas para el tratamiento del paciente basado en los factores de la genética, el ambiente y estilo de vida. Mientras el NRC prefiere el termino “medicina de precisión”, otros aun utilizan medicina Personalizada o ambos términos indistintamente

Nuestro grupo utilizará el término Medicina Personalizada de Precisión (MPP)Entre los nuevos desafíos como así también los beneficios potenciales que ofrece la Medicina Personalizada de Precisión podemos mencionar:

2.1 Los desafíos a corto y largo plazo que se tornan en beneficios a corto y largo plazo:

- Mayor habilidad de los doctores para utilizar la información tanto genética como molecular como parte de la rutina medica (17).

- Mejorar la habilidad de predecir cuales tratamientos serán mas óptimos para los pacientes.

- Mejorar las aproximaciones para prevenir, diagnosticar y tratar un amplio rango de enfermedades.

- Mejor comprensión de los mecanismos subyacentes por los cuales varias enfermedades ocurren.

2.2 Desafíos que al mismo tiempo son beneficios sobre la información tecnológica (IT):

- Nuevas aproximaciones para proteger dentro de la investigación clínica los participantes, particularmente la privacidad y confidencialidad de los datos de los mismos. (18).

- Mejor integración de los records de salud electrónicos (EHRs) para el cuidado de los pacientes, los cuales permitirán que los doctores e investigadores accedan a los datos más fácilmente. (19).

- Diseñar nuevas herramientas, analizar y compartir un largo set de datos médicos.

- Mejorar los test de vigilancia de la FDA, de producción de drogas y otras tecnologías como soporte de la innovación, asegurándose simultáneamente que estos productos sean seguros y efectivos.

2.3 Beneficios a largo plazo:

- Nuevas patentes en ciencia en un amplio rango de enfermedades. Mayor número de participantes de las comunidades de apoyo al paciente, universidades, compañías farmacéuticas y otras.

- Oportunidad de millones de personas de contribuir al avance en la investigación científica. Potenciales beneficios a largo plazo en la investigación en MPP.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

- Rodenburg, E. M, et all.Sex differences in cardiovascular drug-induced adverse reactions causing hospital admissions. Brit J Clin Pharmaco 74, 1045–1052 (2012).

- FDA, FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS).Database. (2015) Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/default.htm. (Accessed: 10th June 2015).

- Rodenburg, E. M., Stricker, B. H. C.& Visser, L. E. Sex-related differences in hospital admissions attributed to adverse drug reactions in the Netherlands. Brit J Clin Pharmaco 71, 95–104 (2011).

- Okon, E., et all Tigecycline-related pancreatitis: a review of spontaneous adverse event reports. Pharmacotherapy33, 63–68 (2013).

- Brown, S. H.et al. VA national drug file reference terminology: a cross-institutional content coverage study. Medinfo: Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 11, 477–81 (2004).

- Hitesh Patel, et all. Trends in hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions in England: analysis of national hospital episode statistics 1998–2005 BMC Clin Pharmacol. 7: 9 (2007).

- Klaas A. Hartholt et all, Adverse Drug Reactions Related Hospital Admissions in Persons Aged 60 Years and over, The Netherlands, 1981–2007: Less Rapid Increase, Different Drugs. PLoS One 5:11(2010).

- Kadoyama, K.et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to anticancer agents: data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system, AERS. J Exp Clin Canc Res 30, 93 (2011).

- Wang, L. W.et all.Standardizing adverse drug event reporting data. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 5, 13 (2014).

- Aitken, M. et all Medicine use and shifting costs of healthcare. A review of the use of medicines in the United States in 2013. (IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics (2014).

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment (2015).

- Patel H et all Trends in hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions in England: analysis of national hospital episode statistics 1998-2005. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 25: 9 (2007)

- Alzu’bi A, et al Personal genomic information management and personalized medicine: challenges, current solutions, and roles of HIM professionals. Perspect Health Inf Manag.1: 11 (2014)

- . Christaki E & Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ The beginning of personalized medicine in sepsis: small steps to a bright future. Clin Genet. 86(1):56-612014

- http://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org).

- http://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org)

- Sridharan Raghavan & Jason L Vassy Do physicians think genomic medicine will be useful for patient care? Per Med 11(4): 424–433 (2014).

- Sharyl J. et all Electronic Health Records and Medical Big Data: Law and Policy. Cambridge University Press (2009)

Menachemi N & Collum TH. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy.4:47-55 (2011).

1 PERSONALIZED MEDICINE

More than six percent of acute hospital admissions are caused by serious adverse reactions to medicines Most common medicines are not effective in treating large numbers of the patients Drugs used for specific treatments are not effective for every patient or group of patients as we expect (1-12). Personalized medicine addresses these challenges, with tailor-made prevention and treatment strategies for individuals and groups. As a result, we have a win-win situation where patients receive the specific therapies that work best for them, and less money is spend on trial and error treatments. The control of healthcare costs is very important since costs across the world are rising, as the population ages. Also, chronic diseases become more prevalent and others spread more quickly as ever before, due to the increased mobility of the world population.

The concept of “personalized medicine” was anticipated in the late 1800s by Canadian physician Sir William Osler who noted “great variability among individuals”; however, the more modern definition has evolved to incorporate personal genomic information into a patient’s clinical assessment and family history to guide medical management (13-15). Current research in this field involve identifying the genetic basis of common diseases, studying how genes and the environment interact to cause human disease, and using biomarkers to facilitate more effective drug therapy (16).

Although there is no universally accepted definition, the Horizon 2020 Advisory Group has defined personalized medicine as “a medical model using characterization of individuals’ phenotypes and genotypes (e.g. molecular profiling, medical imaging, lifestyle data) for tailoring the right therapeutic strategy for the right person at the right time, and/or to determine the predisposition to disease and/or to deliver timely and targeted prevention“. This definition was also used by EU Health Ministers in their Council conclusions on personalized medicine for patients, published in December 2015. Although some personalised medicine approaches have already been introduced into practice in Europe, they are still at an early stage of implementation. Significant paradigm shifts will need to take place in medical research and health care for this innovative area to be fully exploited.

2 PRESICION MEDICINE

Presently, the National Research Council (NRC) of United States, consider personalized medicine is an old term and preferred to use “precision medicine”. For the NRC, precision medicine is “an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person.”

There is a lot of overlap between the definition of the terms precision medicine and personalized medicine. However, there was concern that the term “personalized” could be misinterpreted to imply that treatments and preventions are being developed uniquely for each individual. In precision medicine, the focus is on identifying which approaches will be effective for which patients based on genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. While the NRC prefer the term “precision medicine”, others still use personalize medicine, or the two terms interchangeably.

In our group, we will be using Personalized Precision Medicine (PPM) o Medicina Personalizada de Precisión.

We see new challenges to contribute to Precision Personalized Medicine, and also a number of potential benefits:

2.1 Short and long term challenges that will become short and long term benefits:

- Wider ability of doctors to use patients’ genetic and other molecular information as part of routine medical care (17).

- Improved ability to predict which treatments will work best for specific patients.

- Improved approaches to preventing, diagnosing, and treating a wide range of diseases.

- Better understanding of the underlying mechanisms by which various diseases occur.

2.2 Challenges and the same time benefits from Information technology (IT)

- New approaches for protecting research participants, particularly patients’ privacy and the confidentiality of data (18).

- Better integration of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) for patient care, which will allow doctors and researchers to access medical data more easily (19).

- Design of new tools for building, analyzing, and sharing large sets of medical data.

- Improvement of FDA oversight of tests, drugs, and other technologies to support innovation while ensuring that these products are safe and effective.

2.3 Long term benefits:

- New partnerships of scientists in a wide range of specialties, as well as people from the patient advocacy community, universities, pharmaceutical companies, and others.

- Opportunity for a million people to contribute to the advance of scientific research. Potential long-term benefits of research in PPM.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

- Rodenburg, E. M, et all.Sex differences in cardiovascular drug-induced adverse reactions causing hospital admissions. Brit J Clin Pharmaco 74, 1045–1052 (2012).

- FDA, FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS).Database. (2015) Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/default.htm. (Accessed: 10th June 2015).

- Rodenburg, E. M., Stricker, B. H. C.& Visser, L. E. Sex-related differences in hospital admissions attributed to adverse drug reactions in the Netherlands. Brit J Clin Pharmaco 71, 95–104 (2011).

- Okon, E., et all Tigecycline-related pancreatitis: a review of spontaneous adverse event reports. Pharmacotherapy33, 63–68 (2013).

- Brown, S. H.et al. VA national drug file reference terminology: a cross-institutional content coverage study. Medinfo: Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 11, 477–81 (2004).

- Hitesh Patel, et all. Trends in hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions in England: analysis of national hospital episode statistics 1998–2005 BMC Clin Pharmacol. 7: 9 (2007).

- Klaas A. Hartholt et all, Adverse Drug Reactions Related Hospital Admissions in Persons Aged 60 Years and over, The Netherlands, 1981–2007: Less Rapid Increase, Different Drugs. PLoS One 5:11(2010).

- Kadoyama, K.et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to anticancer agents: data mining of the public version of the FDA adverse event reporting system, AERS. J Exp Clin Canc Res 30, 93 (2011).

- Wang, L. W.et all.Standardizing adverse drug event reporting data. Journal of Biomedical Semantics 5, 13 (2014).

- Aitken, M. et all Medicine use and shifting costs of healthcare. A review of the use of medicines in the United States in 2013. (IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics (2014).

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment (2015).

- Patel H et all Trends in hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions in England: analysis of national hospital episode statistics 1998-2005. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 25: 9 (2007)

- Alzu’bi A, et al Personal genomic information management and personalized medicine: challenges, current solutions, and roles of HIM professionals. Perspect Health Inf Manag.1: 11 (2014)

- . Christaki E & Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ The beginning of personalized medicine in sepsis: small steps to a bright future. Clin Genet. 86(1):56-612014

- http://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org).

- http://www.personalizedmedicinecoalition.org)

- Sridharan Raghavan & Jason L Vassy Do physicians think genomic medicine will be useful for patient care? Per Med 11(4): 424–433 (2014).

- Sharyl J. et all Electronic Health Records and Medical Big Data: Law and Policy. Cambridge University Press (2009)

- Menachemi N & Collum TH. Benefits and drawbacks of electronic health record systems. Risk Manag Healthc Policy.4:47-55 (2011).

Comentarios recientes